This is a book about truth and lies, and the arts of transformation. She even owns up to fantasies of sexual pleasure in the act of violence, refusing to deny the truth even as she realizes its malleability, its inability to withstand the greater caress of good storytelling. She tells stories of a happy-go-lucky ladies’ man uncle so depressed after being jilted that he feels that his “heart is going to leap out of his chest” of the balletic wife of her young karate instructor, a woman whose confidence she rewrote as prose and of seducing an army woman, the repressed overweight daughter of a gangster, taking her by surprise in the shower. The book is integrated with arresting black-and-white photos of the book’s principles and protagonists, the hard-working and depressed women and the hard-drinking men acting tougher even than they are and old before their time.

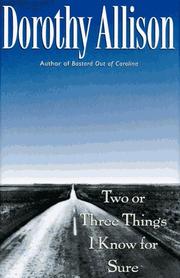

And yet curiously, and at times almost bewitchingly, Allison plays with and cozies up to the notion of story in its ability not just to tell the truth but to conceal it–here, in the simplest possible language, and using her own experiences as a child abuse victim by her stepfather in the American South, she psychoanalyzes the nature of story and story-telling as a means of healing the ego and reinventing the self. I believe Ernest Hemmingway said “All you have to do to be a writer is write one honest sentence.” Well by that definition, and although this slim book with its refrains of the title in different contexts reads almost like a performance piece between two covers–it is in fact reconstructed from texts used in performances used to publicize 1993’s Bastard Out of Carolina–Dorothy Allison is certainly a writer.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)